The Integration of Benton School District

By Cody Berry

On February 4, 1965, the Benton Courier announced that the Benton School Board had officially agreed to comply with Civil Rights regulations in order to obtain federal funds through the National Defense Education Act. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on “race, color, or national origin,” so 1965 was the first year that Benton had to integrate its schools.1 On March 4, 1965, the Benton Courier said that Benton Public Schools had moved “a stride closer to integration,” with their decision to comply with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Superintendent Howard Perrin said that he would attend a meeting in Little Rock with other superintendents throughout Arkansas to discuss the government’s position on the issuance of federal aid and he would report back in April.2

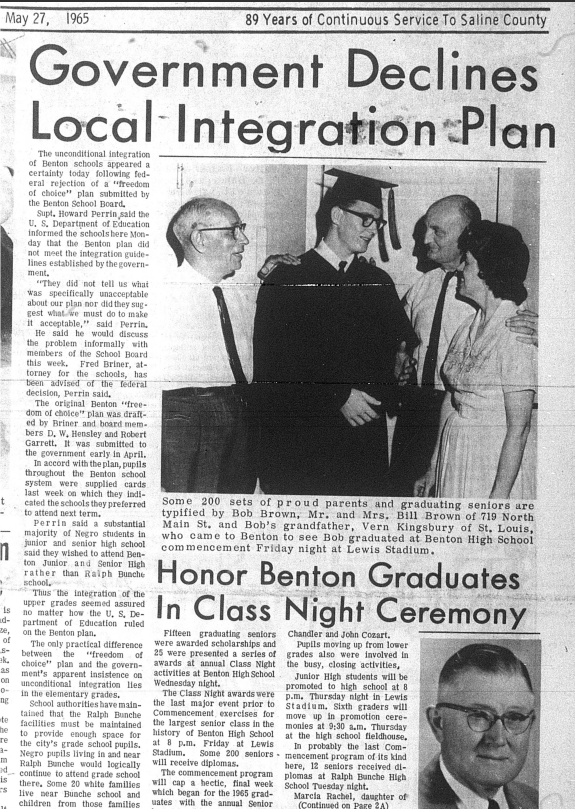

On April 8, 1965, it was announced that the Benton School Board approved an integration plan that gave junior and senior high students the choice of which school they would attend the next year. The plan had no provision for grammar schools, but it allowed pupils to petition for a change from one district to another.3 Superintendent Perrin said that under this plan, white students living in the Ralph Bunche Community wouldn’t be sent to the Ralph Bunche School because conditions there would be “too crowded.”4 On May 27, 1965, the Benton Courier announced that the government had rejected the district’s “Freedom of Choice” integration plan. Bryant reported that it would be fully integrated by next fall.5

Benton’s integration plan was rewritten, and its approval was announced in the Benton Courier on August 19, 1965. Superintendent Perrin said that “about 50 colored students will be enrolled in the senior high school.”6 On September 9, 1965, the Courier reported that Benton Schools had opened “quietly and smoothly.”7 There were eight teachers still working at the Ralph Bunche School, but there were nine black students at Westside Elementary, now Ringgold, and one at Eastside Elementary, now Angie Grant. There were no black students at either Caldwell or Howard Perrin but there were 42 black students at Benton Junior High and 58 at Benton High School.8 Ralph Bunche School closed in 1967.9

Citations:

1 “Schools OK Civil Rights,” Benton Courier, February 4, 1965, p. 1

2 “School Yielding On Integration,” Benton Courier, March 4, 1965, p. 1

3 “Schools Accept Integration Plan For Next Term,” Benton Courier, April 8, 1965, p. 1

4 “Schools Accept Integration Plan For Next Term,” Benton Courier, April 8, 1965, p. 1

5 “Government Declines Local Integration Plan, Benton Courier, May 27, 1965, p. 1; “Bryant Accepts Full Integration,” Benton Courier, May 27, 1965, p. 1

6 “Integration Plan Gets Official Ok,” Benton Courier, August 19, 1965, p. 1

7 “Negro Students Counted at 110,” Benton Courier, September 9, 1965, p. 1.

8 “Negro Students Counted at 110,” Benton Courier, September 9, 1965, p. 1.

9 Saline County History and Heritage Society, Inc., A History of Benton Public Schools, p. 89.